[Review of her exhibition at the Power Plant in C Magazine, #60, Winter 1998.]

Georganne Deen

Many of the best underground comics are simultaneously autobiography and allegory. In Maus, for instance, Art Spiegelman allegorizes autobiography by visually representing the characters (which, on the level of the written text are fully individuated humans) as mice or pigs or cats.

It seems to me that Georganne Deen's paintings are very much influenced by underground comics; at the very least they share the aforementioned quality. But, while the comics tend to move from autobiography to allegory, Deen's work begins with allegory (as befits both high art and the formality of working within a single frame) and moves (both in general and at specific points) into autobiography.

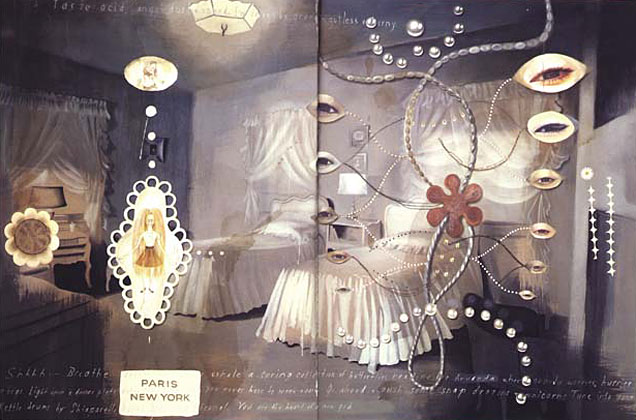

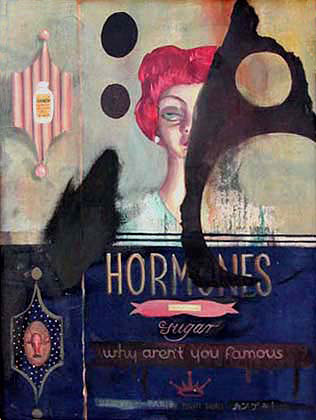

This exhibition brings together, in the words of the beautiful catalogue, "a selection of emblematic works" from each of DeenŐs last three exhibitions: The Mother Load (1994), The Mind Hospital (1996) and Thru the Super Mirror (1997), plus a few works subsequently completed. Many of the works shown are large paintings that combine a literal allegory (the "Child's Garden of Criticism" and the "Learning Tree" in the paintings of the same names) with inset images and texts. The apparent subject of these allegories is the socialization of the female child, but these are harsh, mocking allegories, whose actual subject matter is the child's resistance to her socialization. Or, more specifically, her horror at discovering the endless non-productive expenditure of motherhood, of womanhood. Central images are the harpy-mother wielding a sword and the mother as tree cutting off her own arm and letting the child who was cradled there fall to the ground. Castrating, but also self-castrating, viciously bitter, and moving too slowly to death.

These allegories revolve around images of a mother who is both an actual mother (Deen's, we could presume) and an allegorical figure, "Mother" or "Motherhood." The girl child's depiction of the mother (for these autobiographical allegories are all from the girl child's point of view) shifts in relation to her awareness of her mother's mortality. We could say that they are about waiting for your mother to die. While the allegories are both rebellious and about rebellion, it is a rebellion already soaked in guilt and futility, a resignation to a seemingly inescapable cycle — bourgeois, Oedipal.

The works I find most satisfying are three small commemorative "portraits" of Deen's mother — "That Is All, You May Go," "Merry Xmas (I Can't Hear You Anymore," and "The Dow is Down" — along with two earlier, smaller works that the artist completed in anticipation of her parents' death — "Loss (ha ha)" and "Heirloom Balls."

"Loss" depicts the mother as a satisfied, regal milk-machine: her body is composed of a dozen large breasts; in her hands are two ornate containers from which flow a seemingly endless supply of milk. "Heirloom Balls" depicts the always already castrated father as his genitals. His balls are a simple, elegant looped pencil line on the silk canvas; his penis is sheathed by a tiny crocheted female doll; a stream of expended semen concatenates into a pretty gold chain.